Shortly after composing my last artist statement, I came upon this podcast while listening to old episodes of my favorite audio show, Radiolab. The show fascinated and stunned me, because it so very much provided a clear and timely example of the very complex relationship I have been exploring between humanity, earth, intention, and consequences. As I listened to it in my studio I actually got goose bumps on my arms. If you take a few minutes to hear the segment you will have a clear understanding of my current 2013 work.

Shortly after composing my last artist statement, I came upon this podcast while listening to old episodes of my favorite audio show, Radiolab. The show fascinated and stunned me, because it so very much provided a clear and timely example of the very complex relationship I have been exploring between humanity, earth, intention, and consequences. As I listened to it in my studio I actually got goose bumps on my arms. If you take a few minutes to hear the segment you will have a clear understanding of my current 2013 work.

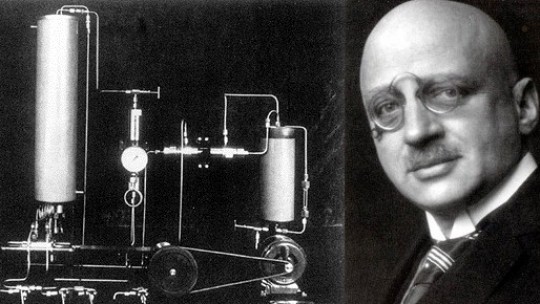

Nitrogen is one of the nutrient elements needed to make cell walls, proteins, and life. Farmers have always known that composting crop waste, animal manure, and even human waste led to better harvests, but these methods were not enough to keep up with the world’s growing population – about 1.5 billion around the turn of the century. Although nitrogen makes up four out of every five atoms in the atmosphere, plant-available nitrogen in the soil is scarce, and there was no way to capture atmospheric nitrogen for plant use. Enter Fritz Haber, a young chemist in Germany, who was intent on solving the biggest problem facing his country: how to feed a growing population. At the time, everyone was starting to worry that humans had maxed out how much food the Earth could produce, until about 1911 when Haber made arguably the most significant scientific breakthrough in human history–how to pull nitrogen out of the atmosphere, which could then be used as fertilizer. They called it “bread from the air” and Haber’s work eventually earned him a Nobel Prize for chemistry. The Haber process is what has enabled our population to grow to seven billion, and today the world produces 100 million tons of synthetic fertilizer per year. It is estimated that half of the average human body is composed of nitrogen that has been through the Haber Process.

Haber also, however, played a major role in the development of chlorine gas and other deadly gases for use in trench warfare during WWl. By 1913, the German chemical giant BASF had a plant operating in Ludwigshaven-Oppau, Germany making ammonia at the rate of 30 metric tons per day to use in explosives, another of Haber’s fields of study. Without question, this technology permitted Germany to continue making explosives and extended the war for many years. During the 1920s, scientists working at Haber’s institute developed the cyanide gas formulation Zyklon A, which was used as an insecticide, and which was later modified by the Nazis to become Zyklon B, used in the gas chambers to kill Jews.

A century ago, when Fritz Haber first learned how to capture nitrogen from the air, synthetic fertilizer seemed like an easy shortcut out of scarcity, delivering a limitless supply of agriculture’s most important nutrient and sustaining a hungry and growing population. Today, runaway nitrogen is suffocating wildlife in lakes and estuaries, contaminating groundwater, and even warming the globe’s climate via emissions of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas 200-300 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. The US fertilizer industry increasingly relies on cheap natural gas to power the synthesis of fertilizer. The gas is extracted by “fracking”—the controversial process of extracting gas from rock formations by bombarding them with water spiked with toxic chemicals. Like any petrochemical activity, generating nitrogen from natural gas is a dirty process. To make fertilizer, ammonia companies not only generate vast amounts of carbon dioxide, they also emit millions of pounds of toxic chemicals each year. Deerfield, Ill.-based CF Industries owns 28 percent of the nitrogen-fertilizer market “in key Corn Belt markets,” according to the company’s website. In Donaldsville, La., the company runs what it calls “North America’s largest” nitrogen-producing facility. The Donaldsville plant lies in so-called “Cancer Alley,” the petrochemical-intensive zone between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that is notorious for its alleged cancer clusters. Donaldsville is in Ascension Parish. As of 2002, Ascension “ranked among the dirtiest/worst 10 percent of all counties in the U.S. in terms of total environmental releases,” according to the pollution-information site Scorecard. According to Scorecard, the worst polluter in the county was CF Industries. Two other fertilizer firms, Triad Nitrogen and PCS Nitrogen Fertilizers, also cracked the top ten, joining German agrochemical giant BASF and Dutch-owned Shell Chemical, among others.

So, the story is not a simple one. In my artistic exploration of these very complex relationships between humanity, earth, intention, and consequences, I make an effort not to be subjective. Of course food is “good” and pollution and overpopulation are “bad,” but it is not the judgment that is as interesting to me as the actions and reactions within the system itself.

3 Comments

Just testing your server and I was totally sucked up into this. Wow.

Now I can’t sleep.

Thanks.

Wow, thanks Jay.

Great concept unveiled in artistic representations of histologic findings in synergy with the laws of thermodynamics. Very Cool!